Difference between revisions of "General Information/IS Distribution"

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

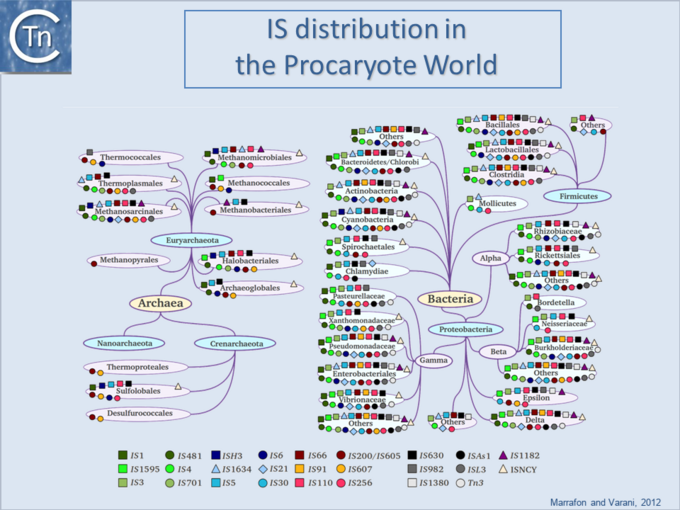

| − | '''<big>I</big>'''Ss are widespread [[:Image:1.6.1.png|(Fig.6.1)]] and can occur in very high numbers in prokaryotic genomes. A recent study concluded that proteins annotated as Tpases, or as proteins with related functions, are by far the most abundant functional class in both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomic and [[wikipedia:Metagenomics|metagenomic]] public databases<ref | + | '''<big>I</big>'''Ss are widespread [[:Image:1.6.1.png|(Fig.6.1)]] and can occur in very high numbers in prokaryotic genomes. A recent study concluded that proteins annotated as Tpases, or as proteins with related functions, are by far the most abundant functional class in both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomic and [[wikipedia:Metagenomics|metagenomic]] public databases<ref><pubmed>20215432</pubmed></ref> [[:Image:1.2.5.png|(Fig.2.5)]]. [[Image:1.6.1.png|thumb|center|680x680px|'''Fig.6.1.''' IS distribution in the prokaryotic world. |alt=|border]]Since the last surveys (e.g. <ref>Chandler M, Mahillon J. Insertion Sequences Revisited. In: Craig NL, Lambowitz AM, Craigie R, Gellert M, editors. Mobile DNA II. American Society of Microbiology; 2002. p. 305–366. </ref><ref><pubmed>9729608</pubmed></ref>) many new ISs have been identified largely as a result of the massive increase in available sequenced prokaryotic genomes. Careful analysis of a number of these has also revealed that some genomes contain significant levels of truncated and partial ISs devoid of Tpase genes. These genomic "scars" represent traces of numerous ancestral transposition events. However, genome annotations are often based simply on the presence of Tpase genes (e.g. <ref><pubmed>17251179</pubmed></ref>) and do not include the entire DNA sequence with the IS ends. Indeed, a significant number of solo IS-related '''I'''nverted '''R'''epeats (IRs) have been identified in various genomes. Small IS fragments are rarely taken into account even though they can provide important insights into the evolutionary history of the host genome [[:Image:1.6.2.png|(Fig.6.2)]], [[:Image:1.6.3.png|(Fig.6.3)]] and [[:Image:1.6.4.png|(Fig.6.4)]]. Not only can this seriously impair studies attempting to provide an overview of the evolutionary influence of TEs on bacterial and archeal genomes, but such fragments may encode truncated proteins and these could influence gene regulation (e.g. <ref><pubmed>16672366</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>20309721</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>19390626</pubmed></ref>). In bacteria <ref><pubmed>2154486</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>11705917</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>17078817</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>8226636</pubmed></ref> and eukaryotes<ref><pubmed>1662417</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>8391505</pubmed></ref> truncated transposases have been shown to inhibit transposition. One example where annotation of IS fragments has provided important information is in the obligatory intracellular insect endosymbiont, ''[[wikipedia:Wolbachia|Wolbachia]]'', which also carries high numbers of full-length ISs. The sequence divergence observed suggests that several waves of IS invasion and elimination have occurred over evolutionary time <ref><pubmed>21940637</pubmed></ref>. |

<center> | <center> | ||

{| | {| | ||

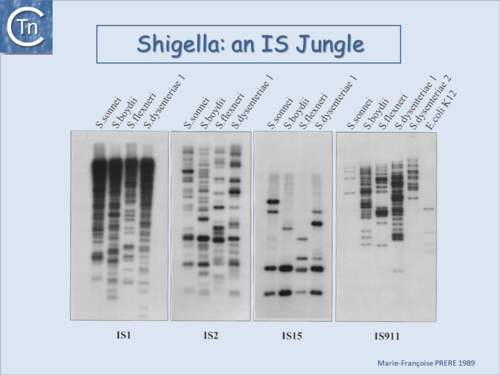

| − | |[[Image:1.6.2.png|thumb|center|500x500px|'''Fig.6.2.''' <i>[[wikipedia:Shigella|Shigella]]</i> an IS jungle. A Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of various ''Shigella'' species and hybridization using radioactively labeled probes of insertion sequences [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1R IS''1''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS2 IS''2''] ([[IS Families/IS3 family|IS''3'' family]]), [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS15 IS''15''] ([[IS Families/IS6 family|IS''6'' family]]) and IS''911'' (IS''3'' family).<br /> |alt=|border]] | + | |[[Image:1.6.2.png|thumb|center|500x500px|'''Fig.6.2.''' <i>[[wikipedia:Shigella|Shigella]]</i> an IS jungle. A Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of various ''Shigella'' species and hybridization using radioactively labeled probes of insertion sequences [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1R IS''1''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS2 IS''2''] ([[IS Families/IS3 family|IS''3'' family]]), [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS15 IS''15''] ([[IS Families/IS6 family|IS''6'' family]]) and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS911 IS''911''] ([[IS Families/IS3 family|IS''3'' family]]).<br /> |alt=|border]] |

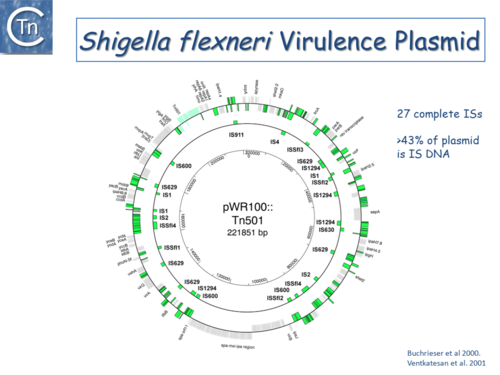

|[[Image:1.6.3.png|thumb|center|500x500px|'''Fig.6.3.''' The <i>[[wikipedia:Shigella_flexneri|Shigella flexneri]]</i> virulence plasmid circular map. The outer circle indicates (in green) both full length IS of different types and IS fragments, scars of previous transposition and recombination events, and IS decay. The second circle shows the location of complete IS copies. The inner-circle shows plasmid coordinates. |alt=|border]] | |[[Image:1.6.3.png|thumb|center|500x500px|'''Fig.6.3.''' The <i>[[wikipedia:Shigella_flexneri|Shigella flexneri]]</i> virulence plasmid circular map. The outer circle indicates (in green) both full length IS of different types and IS fragments, scars of previous transposition and recombination events, and IS decay. The second circle shows the location of complete IS copies. The inner-circle shows plasmid coordinates. |alt=|border]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

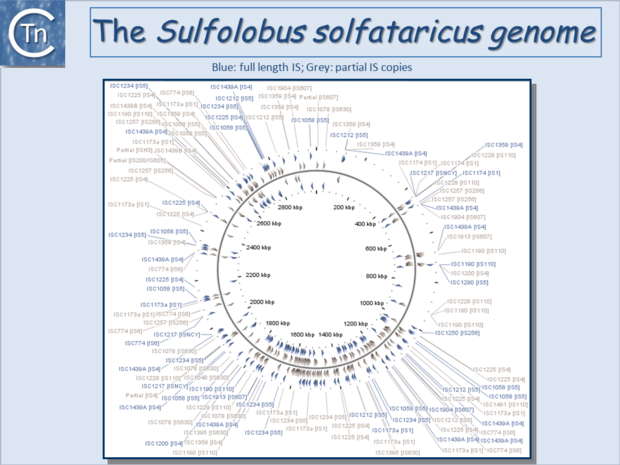

| − | [[Image:1.6.4.png|thumb|center|620x620px|'''Fig.6.4.''' The <i>[[wikipedia:Sulfolobus_solfataricus|Sulfolobus solfataricus]]</i> P2 circular genome representation showing Complete IS (blue) and IS fragments (grey/brown). The IS family to which each IS belongs is shown in brackets. |alt=]]</center> | + | [[Image:1.6.4.png|thumb|center|620x620px|'''Fig.6.4.''' The <i>[[wikipedia:Sulfolobus_solfataricus|Sulfolobus solfataricus]]</i> P2 circular genome representation showing Complete IS (blue) and IS fragments (grey/brown). The IS family to which each IS belongs is shown in brackets. |

| + | |||

| + | For a more detailed visualization, please go to I[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISbrowser/script_php/graphic_display.php?ac_number=NC_002754 Sbrowser Graphical Display of ''S. solfataricus'' P2 genome]. |alt=]]</center> | ||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| − | < | + | {{Reflist|32em}} |

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | {{TnPedia}} | ||

Latest revision as of 12:29, 5 December 2022

ISs are widespread (Fig.6.1) and can occur in very high numbers in prokaryotic genomes. A recent study concluded that proteins annotated as Tpases, or as proteins with related functions, are by far the most abundant functional class in both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomic and metagenomic public databases[1] (Fig.2.5).

Since the last surveys (e.g. [2][3]) many new ISs have been identified largely as a result of the massive increase in available sequenced prokaryotic genomes. Careful analysis of a number of these has also revealed that some genomes contain significant levels of truncated and partial ISs devoid of Tpase genes. These genomic "scars" represent traces of numerous ancestral transposition events. However, genome annotations are often based simply on the presence of Tpase genes (e.g. [4]) and do not include the entire DNA sequence with the IS ends. Indeed, a significant number of solo IS-related Inverted Repeats (IRs) have been identified in various genomes. Small IS fragments are rarely taken into account even though they can provide important insights into the evolutionary history of the host genome (Fig.6.2), (Fig.6.3) and (Fig.6.4). Not only can this seriously impair studies attempting to provide an overview of the evolutionary influence of TEs on bacterial and archeal genomes, but such fragments may encode truncated proteins and these could influence gene regulation (e.g. [5][6][7]). In bacteria [8][9][10][11] and eukaryotes[12][13] truncated transposases have been shown to inhibit transposition. One example where annotation of IS fragments has provided important information is in the obligatory intracellular insect endosymbiont, Wolbachia, which also carries high numbers of full-length ISs. The sequence divergence observed suggests that several waves of IS invasion and elimination have occurred over evolutionary time [14].

Fig.6.2. Shigella an IS jungle. A Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of various Shigella species and hybridization using radioactively labeled probes of insertion sequences IS1, IS2 (IS3 family), IS15 (IS6 family) and IS911 (IS3 family). |

Fig.6.3. The Shigella flexneri virulence plasmid circular map. The outer circle indicates (in green) both full length IS of different types and IS fragments, scars of previous transposition and recombination events, and IS decay. The second circle shows the location of complete IS copies. The inner-circle shows plasmid coordinates. |

Bibliography

- ↑

- ↑ Chandler M, Mahillon J. Insertion Sequences Revisited. In: Craig NL, Lambowitz AM, Craigie R, Gellert M, editors. Mobile DNA II. American Society of Microbiology; 2002. p. 305–366.

- ↑ Mahillon J, Chandler M . Insertion sequences. - Microbiol Mol Biol Rev: 1998 Sep, 62(3);725-74 [PubMed:9729608] [DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ Cordaux R, Udit S, Batzer MA, Feschotte C . Birth of a chimeric primate gene by capture of the transposase gene from a mobile element. - Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A: 2006 May 23, 103(21);8101-6 [PubMed:16672366] [DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ Wray J, Williamson EA, Royce M, Shaheen M, Beck BD, Lee SH, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R . Metnase mediates resistance to topoisomerase II inhibitors in breast cancer cells. - PLoS One: 2009, 4(4);e5323 [PubMed:19390626] [DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ Salvatore P, Pagliarulo C, Colicchio R, Zecca P, Cantalupo G, Tredici M, Lavitola A, Bucci C, Bruni CB, Alifano P . Identification, characterization, and variable expression of a naturally occurring inhibitor protein of IS1106 transposase in clinical isolates of Neisseria meningitidis. - Infect Immun: 2001 Dec, 69(12);7425-36 [PubMed:11705917] [DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ de la Cruz NB, Weinreich MD, Wiegand TW, Krebs MP, Reznikoff WS . Characterization of the Tn5 transposase and inhibitor proteins: a model for the inhibition of transposition. - J Bacteriol: 1993 Nov, 175(21);6932-8 [PubMed:8226636] [DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ Vos JC, van Luenen HG, Plasterk RH . Characterization of the Caenorhabditis elegans Tc1 transposase in vivo and in vitro. - Genes Dev: 1993 Jul, 7(7A);1244-53 [PubMed:8391505] [DOI]

- ↑